DIY Gatsby: Worth it?

This is Part IV of a series where we'll look into how kimmo.blog works. Part IV focuses on the pros and cons of the DIY build system.

Motivation has been covered in Writing, or coding.

DIY vs Gatsby

The disclaimers in Part I briefly mentioned this already, but it's worth recapping. Gatsby is a production-ready tool and in this series we built only a part of it.

Let's look at a classic feature comparison table.

| Feature | DIY | Gatsby |

|---|---|---|

| Site generator | ||

| Great end-user performance | ||

| MDX | ||

| Frontend routing | ||

| Custom data sources | ||

| Documentation | ||

| Community |

The DIY solution has a similar core functionality, but lacks in some areas. Nevertheless, the tool works and successfully builds this blog in a similar way Gatsby would. The solutions are similar, but it's not a direct comparison.

Let's go through the good and the bad.

Good #1: Technical simplicity

My thoughts are inevitably biased because I've incrementally gathered knowledge of the system while developing the blog. Knowing that I'd still claim that the build system is pretty simple considering how much it does.

The simplicity has been achieved by keeping the number of abstraction levels to a minimum. A few examples:

- Build steps operate on directories and files

- Each build step is a narrowly scoped CLI command

- ES6 modules are leveraged to keep bundling simple

Part of the minimalism can be attributed to the lack of varying use cases. Gatsby supports thousands of use cases, while the custom-tailored tooling caters just this blog.

Something to keep in mind is that simple doesn't equal easy. While the tooling is simple, it doesn't automatically mean a better choice for a new website. The lack of documentation and community around the tooling would likely total to a net negative in comparison to widely used tools like Gatsby or react-static.

Good #2: No GraphQL in simple workflows

Some simple tasks are overly complicated to achieve in Gatsby. The reason for that in my opinion is the GraphQL layer. It's applicable when fetching more complex data from a content management system but not so much for retrieving local .mdx files.

The documentation for using MDX content in Gatsby starts with configuring the gatsby-source-filesystem plugin. After that, you'll spend time reading the documentation for accessing the file system via GraphQL queries. It's not a very common pattern after all.

With the DIY system, you access the files as you'd normally do:

const files = await glob("posts/*.mdx");const promises = files.map((name) => fs.promises.readFile(name, { encoding: 'utf8' }));const contents = await Promise.all(promises);The argument might not be a fair one, since it's completely understandable why Gatsby does this. They rely on GraphQL as the single tech for accessing data. It's a smart choice for the average use case — accessing data from varying sources.

Good #3: Skipping an abstraction layer

Gatsby has over 2500 plugins. Many of them are tremendous and greatly simplify otherwise complicated workflows. For example gatsby-plugin-image adds responsive images automatically on your website.

The downside of plugins is that they introduce an unnecessary Gatsby-specific abstraction on top of the original problem. For example, markdown processing is already complicated enough with remark and unified, but Gatsby makes it even more complicated with its own set of plugins.

Even in a Gatsby project, I prefer to solve some problems natively instead of using a plugin. For example, it might be simpler to just add a favicon.svg in the static directory, instead of using a plugin for that.

In the DIY setup, we skip an abstraction layer. The code directly uses rss, remark, and other libraries. There's no plugin API or configuration format in the middle to learn.

Good #4: Rollup bundling

By leveraging Rollup and ES6 modules, the bundling becomes intuitive. Instead of a single large bundle.js, source code and its dependencies are bundled into separate cacheable files.

ES6 modules are used in the development environment as well as in the production site. Because this is a developer-focused blog, I can just ignore the browsers that don't support ESM.

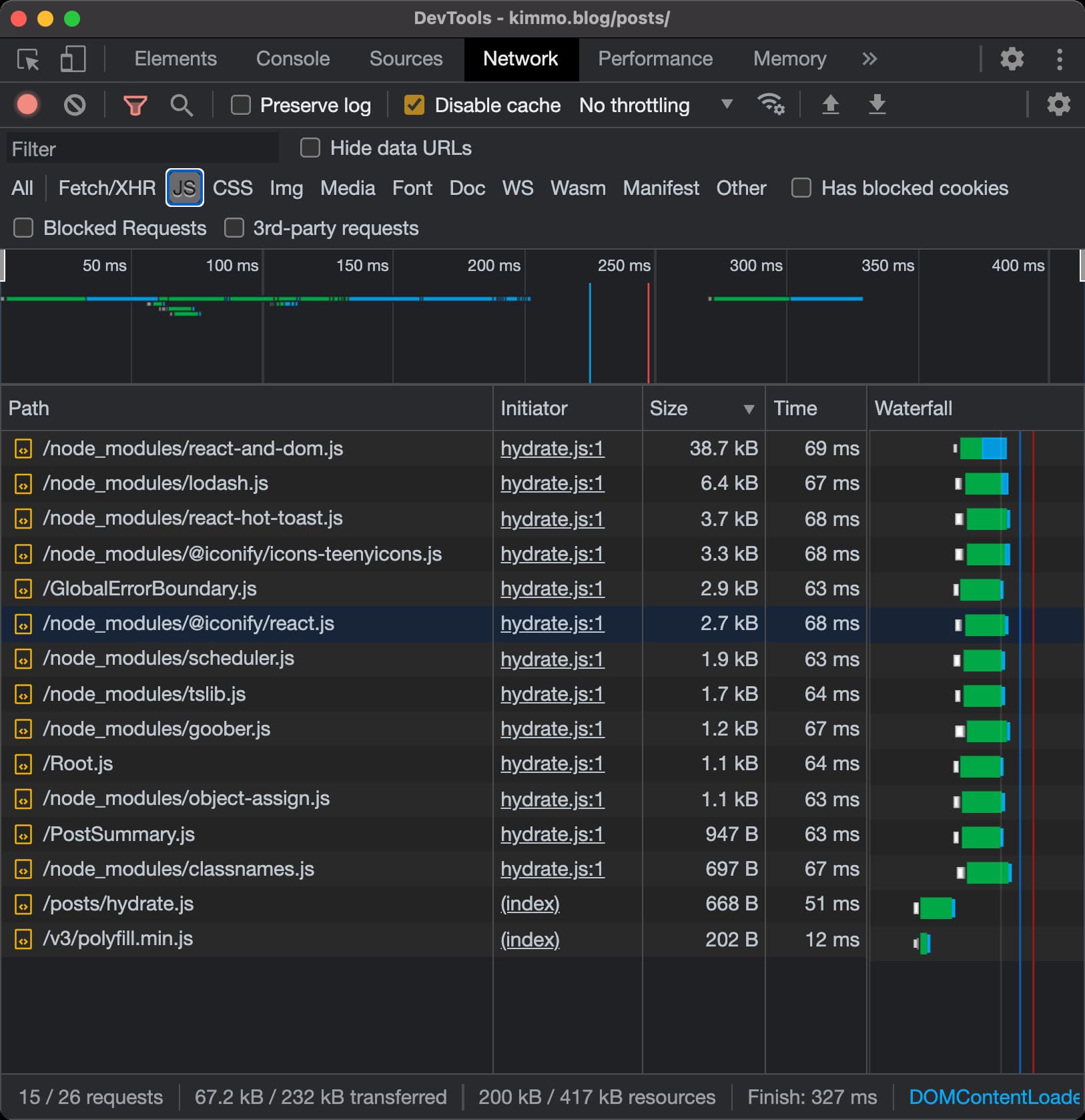

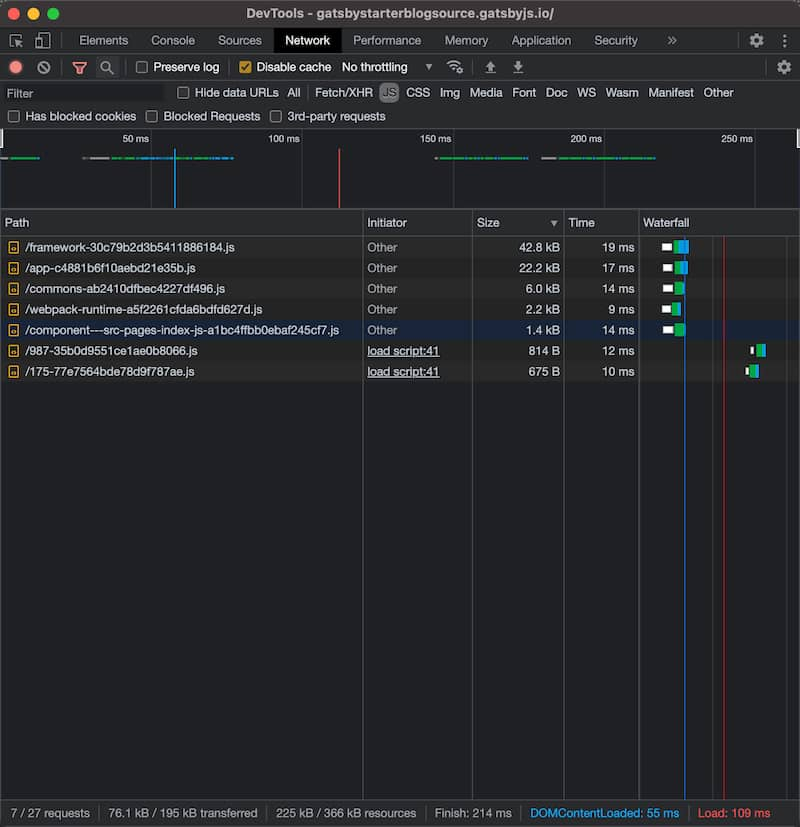

The screenshots below show which JS files are loaded for kimmo.blog in comparison to Gatsby starter blog.

Although the starter blog doesn't have many components, Gatsby uses Webpack to bundle components into a few different bundles. This process leads to fewer individual JS files but makes the bundles quite cryptic. Gatsby's documentation explains how bundles are formed in great detail.

The DIY version on the other hand has a predictable mapping from source code to built version of the site:

Simple and intuitive.

The bundling is achieved with Rollup's manual bundle chunking. The /node_modules/ directory is not a valid npm-usable directory, but just a regular directory that groups bundles of external dependencies under a familiar name.

Bundling modules in the described way has an awesome side-effect: the network panel can be directly used as to see which dependencies weigh the most. No need for an external bundle analyzer tool.

It would be fair to question whether this actually matters. Production bundles are anyways going to be minified and optimizing software distributables should be a higher priority than developer convenience in the production environment. I'd have to agree. But still, if it's possible to get equal performance with a simpler solution, I'll take it!

Sounds like a neat setup, but why isn't it used more widely?

One big reason is that ES6 modules are a fairly new standard: initial browser support landed in 2017. Fortunately, the tools are improving every day. Snowpack uses ESM exclusively and many frontend libraries in npm are shipping only the ESM bundles for their latest versions.

Another reason may be that the approach used to be a performance killer in HTTP/1.1. However, nowadays doing multiple requests is just fine! Multiplexing in HTTP/2 solved the network bottleneck.

There's one more possible reason that will be covered in "Bad #5: Chaining requests at page load".

Bad #1: Messy architectural boundaries

Gatsby as a framework provides boundaries and a well-defined API. There's a strict border between your application code and the framework code.

The same cannot be said from the DIY approach. As much as I tried to keep the boundaries clear, the blog code knows too much about the supposedly generic site generator and vice-versa.

Bad #2: Onboarding experience

Let's say you'd have to onboard a new developer into a website project. Would you rather guide them to read Gatsby's documentation or spend days explaining how a custom system works?

I think we both know the answer. There's even a good chance that a new developer would already have experience with Gatsby.

Bad #3: Everything consumes time

While writing a script that generates an RSS feed is fairly straightforward, it takes development time. Small tasks add up. A bunch of time is wasted building mundane supporting functionality, instead of the actual website.

In the do-it-yourself approach, you'll gain a deep understanding of each little part of the build tool. It's likely to be useful knowledge even in the following projects, but unfortunately, it doesn't remove the maintenance burden later. The DIY solution has no public issue discussion, let alone contributors opening PRs that help the whole community.

Bad #4: Slow iteration

The downside of simplicity is slowness. Many other build systems leverage caching, in-memory data structures, and complex abstractions to improve performance. Since the DIY approach opted for simpler abstractions, the cost is sluggish iteration during development.

The file-based build pipeline could be improved in the future, but at the time of writing, it took around 8 seconds from a code change to seeing it in the browser. That's a tad too much.

Bad #5: Chaining requests at page load

While the Rollup ESM setup is a pleasant development experience, there's a downside. Using imports causes request chaining in the critical render path. The browser needs to do multiple request-response round trips to fetch all relevant files in the module tree. For example:

Browser loads index.html (1) which refers to a JS module.

<script type="module" src="./hydrate.js"></script>Browser requests hydrate.js (2) from the server and parses the file. There's a new import inside.

import App from "./app.js"Browser requests app.js (3) from the server. There's yet another import.

import PostsPage from "./pages/Posts.js" // (4)This continues until we've reached the final leaf module in the import tree.

The example had 4 round-trips between the browser and the server. The process is slow and web performance tools often complain about chaining requests for a reason. I'm not sure what the real fix would be but maybe import maps will help in the future.

If you know of a solution, I'd be curious to hear about it!

Conclusion

Let's summarize the arguments above.

Good:

- Technical simplicity

- No GraphQL for simple workflows

- Skipping an abstraction layer

- Rollup bundling

Bad:

- Messy architectural boundaries

- Onboarding experience

- Everything consumes time

- Slow iteration during development

- Chaining requests at page load

The final site builds ended up being quite similar in size. Gatsby wins in end-user performance by a small margin since it supports frontend routing. The routing allows faster page changes after the initial load.

So, what were the key takeaways?

For me, building a site generator was definitely worth it. I learned about ES6 modules, Gatsby, web performance, and much more. It also supported my goals for the blog and proved to be an enjoyable coding exercise.

For a professional project, I'd definitely recommend adopting more widely used tools like Gatsby or react-static.

Sometimes the goal itself is to walk the unbeaten path. I'll let you decide if that's the case or not.